by Grace McConnell, Wyatt Miller, Peyton Spellacy and Meghan McCloskey

SYRACUSE, N.Y. (NCC NEWS) – When Cynthia Long woke up in SUNY Upstate Hospital following her kidney transplant, her main focus was on her now-functional kidney. She said she had been close to dialysis and felt a switch in her body following the transfer.

Long’s new kidney was strong but closing the stomach wound raised issues. She stayed in the hospital for a week being monitored with a packed open wound. After that week, a different surgeon than the one who performed her surgery visited her room. They wanted to open the wound back up to see if they could improve the closure.

Terrified of potential infection, she agreed to the second surgery.

“The kidney was fine, the kidney’s been great,” Long said. “It was just the closure. And they operated on me again, so I was in there again for this thing to heal up. I ended up with a hernia because I guess they couldn’t pull enough skin or whatever to get it to close.”

Although her surgery happened two years ago, Long still struggles because of her hernia to this day.

In total, Long’s time at Upstate cost $880,000, which became $53,000 after insurance. She was able to pay about $26,000 after draining her own savings, but that was it. Her previous injuries and current hernia meant that Long couldn’t work with furniture like she had done previously, and therefore couldn’t make money to pay off her hospital bills.

Despite keeping up with the costs of her copay and after visits, Long was unable to pay the remaining $27,000 of her hospital bill. Not only is she unable to, but she doesn’t believe that all the cost should fall on her after a mistake made by Upstate. She let Upstate know this, but still was eventually served a lawsuit by them.

Cynthia Long was just one of the many vulnerable patients targeted by the hospital’s search to collect and obtain medical debt. Research by Community Service Society (CSS) profiling Upstate Hospital in 2022 concluded that “Upstate Hospital’s medical debt practices indicated that it is an outlier – suing more patients than any other hospital in New York State.”

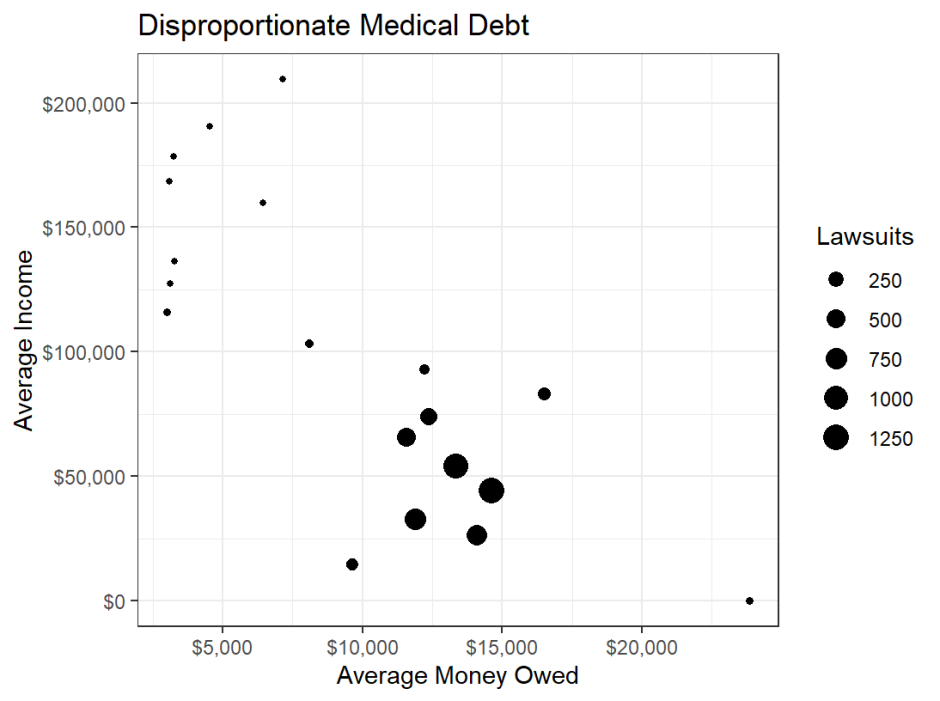

Our team looked through over 5,000 lawsuits by Upstate to New York residents from the years 2020 to 2023. Further analysis of that data revealed that the hospital is disproportionately suing lower income communities. This is in addition to research done by the Urban Institute that proved the largest racial/ethnic disparities in rates of medical debt is seen in Central New York.

The Spotlight Team has reached out twice to officials with Upstate for a comment regarding our investigation but never heard back.

Long worked an office job but had to leave because she was not able to work around others during the pandemic. She took a part-time job at Wegmans bagging groceries but can no longer do that because lifting groceries with her hernia is too difficult.

She has gone back to get her hernia scanned and it is growing, but apparently not enough to be considered an emergency. Long plans on getting a surgery to get it removed, but is worried about having another hospital bill to pay off.

Her fear is warranted, and common among those facing medical debt. In a survey done by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), they found that adults with health care debt are more than twice as likely as those without debt to postpone or skip getting needed health care because of the cost. Medical debt often triggers a cycle of financial burden as those in debt cut costs in other aspects of their life. Around 63% of adults in debt have cut spending on food, clothing, and other basics while 48% reported having used all or most of their savings in paying back debt.

Nonprofit hospitals are meant to serve the community they are a part of through health care services. Our investigation indicates Upstate is doing the opposite through its alleged targeting of the vulnerable population of the Syracuse and Central New York area.

The median household income in Syracuse is $43,584, according to the 2022 census. But, based on the Spotlight Team’s findings, the neighborhood average for median household income on the receiving end of these lawsuits since 2020 is $31,558. That means Upstate seems to be disproportionately suing poorer communities in Syracuse.

Upstate is a state-owned, public hospital. This means that any lawsuits issued by them are sent to the New York Attorney General’s office, where it is verified, filed and sent out. Upstate’s policy is that they will turn to legal action following six months after a hospital visit and after attempting to reach out to a patient three times.

All hospitals in New York are required by federal law to provide financial assistance or payment plans and are given money from the government to do so. Nonprofit hospitals like Upstate are required to provide charity care.

No hospital, however, is required to spend a minimum amount towards financial assistance in order to get their tax exemptions.

This is where issues arise, because hospitals have been leaving patients uninformed for their own monetary gain. Under Upstate’s “frequently asked questions” page, the hospital answers exactly how one can set up a payment plan and the process of qualifying for financial assistance. If this were information explicitly shared with patients, would it need to be frequently asked about?

A source who has asked to remain anonymous was sued for $12,000 by Upstate following their time in and out of the hospital during COVID. They were traveling when Upstate had sent them the letters preceding a lawsuit. They were also not expecting their bill to be so large because they were under the impression that insurance would be covering a most of the cost.

That was when they found out their employer canceled their insurance during the pandemic, so it showed up null and void on Upstate’s records. This person decided to call the Attorney General’s office through Upstate to prevent the lawsuit from further escalating with a court date.

The letters being sent out told them to contact the Attorney General’s office to work out a payment agreement, but all additional information about figuring things out before court date came from them, not Upstate.

Open communication from the hospital about options for payment plans or financial assistance would act as a resource for a patient rather than become a new thing for them to worry about during a stressful time.

Various states across the United States have fast-track programs of presumptive eligibility for patients, helping them qualify for financial assistance automatically. In Maryland, hospitals are required to view patients already enrolled in other need-based programs for low-income residents as qualifying for free care.

Illinois has a presumptive eligibility policy that outlines categories demonstrating financial need that automatically consider a patient as requiring assistance. Oregon’s nonprofit hospitals must screen patients for presumptive eligibility if they are uninsured or owe more than $500. And in Minnesota, uninsured patients are scheduled an appointment with an application counselor in order to make the process of applying for financial assistance easier.

Many of these policies were enacted within the past five years, part of a growing advocacy movement to protect Americans against the issue of medical debt. It has been a growing topic of conversation, and therefore, a topic of research. And one of the biggest things being looked into was the goal of hospitals in suing patients.

The conclusion: most hospitals aren’t.

In New York, Upstate is an outlier because a lot of hospitals are not suing their patients at the same rate. The hospitals within the Syracuse area are Upstate, Crouse Hospital, and St. Joseph’s. According to data from CSS, Crouse Hospital sued 672 patients in 2019, 46 patients in 2020, and no patients in 2021-2022. St. Joseph’s sued six people in 2019, five in 2020, and three in 2021. Upstate filed 1,562 lawsuits in 2019 alone.

Maanasa Kona, an assistant research professor at Georgetown University’s Center of Health Insurance Reforms, confirmed that there is no proven reason as to why hospitals are suing patients, just theories.

“I think it is a question that a lot of people who are advocates in this space have sort of struggled with because the returns on this outstanding debt are just so minimal and the dollar amounts per debt tend to be small for the most part,” said Kona. “So it begs the question, why is it worth going through all this?”

The colors in this interactive map of Syracuse indicate how many medical debt lawsuits have been brought against people in each zip code. The neighborhoods that were targeted most live in neighborhoods that have median incomes well below the median for the city of Syracuse.

Some of the most damaging ways hospitals impact the lives of the patients they sue is through medical debt affecting credit scores, garnishing wages and placing liens on people’s homes as a form of collection. If hospitals were to benefit from these lawsuits, it would be from these methods. One reason Upstate stands out, apart from the large number of lawsuits compared to other hospitals, is because of its continuation of lawsuits despite many New York hospitals no longer suing their patients or suing only a single-digit number of patients.

In 2022, Gov. Kathy Hochul passed a legislation prohibiting health care providers in New York from collecting medical debt via wages and home ownership. Then in December of 2023, another legislature was signed that made it so medical debt would not affect credit scores. This means that New York hospitals, such as Upstate, can no longer profit from medical debt in that way.

Hochul’s latest proposal would ban hospitals in New York from suing anyone with an income under 400% of the poverty line. Additionally, it would extend the time that hospitals must wait before sending unpaid bills to collections to 180 days, prevent hospitals from selling debt to third parties, allow people between 300% and 400% of the poverty line to qualify for financial aid, and open financial aid to uninsured people whose medical costs are greater than 10% of their gross annual income.

According to Kona, providing medical debt protection is just a Band-Aid for the larger issue at hand, and medical debt was never meant to turn into a secondary form of insurance.

“At the end of the day, I think that medical debt protections are important and essential, and states and governments should focus on making them strong and ensuring that people are covered,” said Kona. “But I think on the front end, it’s really, really important to manage health care costs and make sure it doesn’t even get to this place in the first place.”

Many eyes have been on Upstate recently following the release of multiple research reports and articles calling attention to the large number of lawsuits they sent out. While there has been a decrease in lawsuits being sent out, there is no guarantee that the practice will not start back up again once the public uproar has died down. If Hochul’s most recent proposal passes, it will limit a hospital’s ability to sue low-income patients.

Long is not out to get Upstate. In fact, she is very grateful for them, and will continue to go there for treatment in the future. She just wants to make sure that she’s only paying for the things she’s responsible for.